Built as a Roman fort, by the fifteenth century Pevensey Castle was being used as a state prison. We look at some of the most important prisoners who were kept there.

The beginings of Pevensey Castle

On the East Sussex coast sits the ruins of one of England’s least well-known and yet most significant castles. Once perched on a peninsula surrounded by sea and salt marches, it was one of several Saxon Shore forts built around AD290 possibly by one of the two self-proclaimed Emperors of Britain, Carausius and Allectus, as a defence against a counter attack by the government in Rome. It now lies a mile from the coastline but still retains some of its original Roman walls, a rarity in England.

It was known by the Romans as Anderida, but at some time after their withdrawal it became linked with a Saxon resident named Pefen and adopted the name Pefeneã meaning River of Pefen.

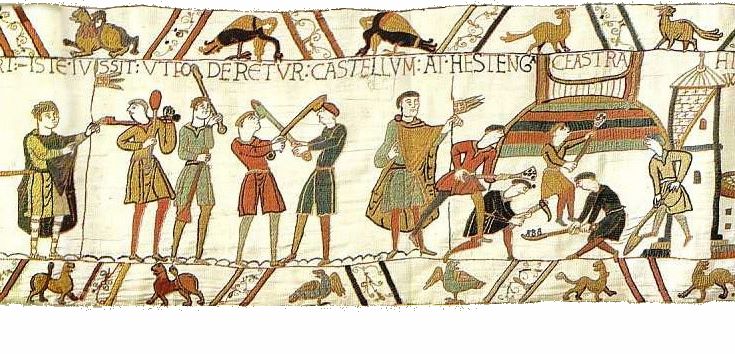

In 1066 William of Normandy chose Pevensey Bay as the place to land and launch his invasion of England and it would be the site of the first Norman castle in the country, built within the Roman walls. Over the centuries, ownership passed between the crown, its allies and its enemies, and it took on new strategic importance, remaining a key coastal defence until the sea began to recede around 1300.

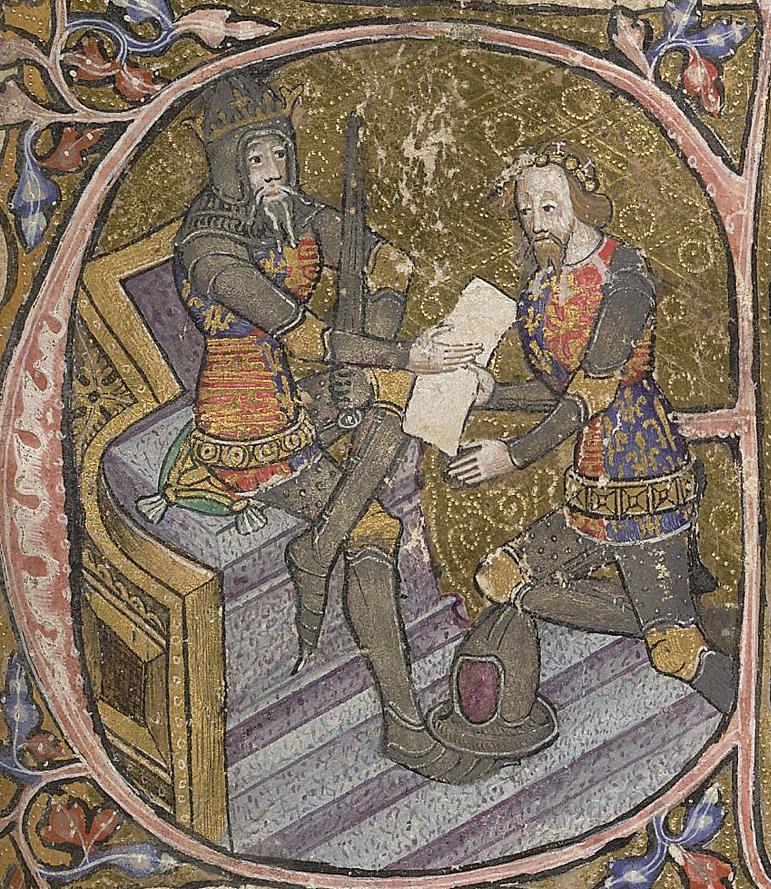

In 1394 Sir John Pelham become its Constable, holding it for the Lancastrian cause during Henry Bolingbroke’s invasion. Henry IV personally addressed him as his ‘dear esquire’ and awarded his unshakable loyalty with various grants and ceremonial honours and by making him one of the five executors of his will.

He also entrusted him with some particularly important prisoners: a duke, earl, king and witch.

The duke: Edward, duke of York (1405)

Edward was the grandson of Edward III through his fourth surviving son, Edmund of Langley, duke of York. Edward was a close supporter and friend of his cousin, Richard II, from whom he received numerous titles, grants and land, including the dukedom of Aumale in 1397. When Richard and their mutual cousin Henry Bolingbroke fell out, Edward supported the king and did well from Bolingbroke’s exile from England in 1398, when he received lands which were part of the Lancastrian inheritance. He was with the king in Ireland when Bolingbroke invaded and has been identified as responsible for advising Richard to split the army, an action which helped bring about his downfall. The king’s army collapsed around him – Edmund of Langley, who had been left in charge of England, surrendered to Henry and Edward soon followed his father’s example and deserted Richard.

Although he spent a short period in the Tower of London and lost his Aumale title, Edward was spared Richard’s fate, who was removed from power and assassinated shortly afterwards. The new Henry IV was prepared to accept Edward’s allegiance and allowed him to succeeded his father to become the 2nd duke of York in 1402.

However, it was not long until Edward fell into trouble again with his royal cousin. Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March, had once been the heir presumptive to Richard II and he and his brother Roger were kept in close custody by Henry IV at Windsor Castle. In a scheme known as the Tripartite Indenture, their uncle, Sir Edmund Mortimer, was part of a plot to overthrow Henry IV and divide England and Wales between himself, Owain Glyndŵr and Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland. As part of the plan, Edmund and Roger were freed on 13 February 1405 but they were quickly discovered on their way to Wales. Party to the abduction was York’s sister, Constance, the Countess of Gloucester, who soon accused her brother of being involved. At first he denied it but later admitted that he had known about the plot. Henry took decisive action and Edward was arrested and sent to Pevensey Castle.

Edward was held prisoner for seventeen weeks, kept in the better parts of the castle rather than the flooded dungeons. Sir John’s loyalty to the king never flinched, but he did help Edward to deliver personal letters to the king, enabling him to petition for his release. The relationship would last, with York making Pelham a trustee of his estates and, in 1412, delegating him part of the lordship of Tynedale and Wark. In 1415 York gave Pelham freehold of his London residence and took his illegitimate son with him on the French campaign. Evidence in Edward’s will also indicates that he formed a bond with another gaoler, Thomas Playsted who was left a gift ‘for the kindness he showed me when I was in ward at Pevensey’.

Edward was able to rebuild his relationship with the king and on 8 December 1405 he was restored to his lands with Pelham being rewarded (and compensated) by receipt of the Chief Stewardship of the duchy of Lancaster’s southern estates.

York’s loyalty did not waiver again although his younger brother Richard, earl of Cambridge, was beheaded on 5 August 1415 for his part in the Southampton plot to overthrow Henry V. Ironically, York died a hero at the Battle of Agincourt on 25 October 1415.

The Duke of York was also lost,

For his king, no foot would he flee

Til his bascinet to his brain was bent.

The earl: Edmund, earl of March (1406-1409)

Edmund was only thirteen at the time of the Tripartite Indenture when he and his brother were abducted from Windsor Castle and the event threw the boys back into the spotlight.

Edmund was descended from Edward III through his second surviving son Lionel, duke of Clarence, and, as such, was a better claimant to the throne than Henry IV who was descended from Edward III’s third surviving son, John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster. However, Edmund’s claim was through a female line, giving Henry the edge. But Henry could not ignore the young March and his brother, and he had them kept in the custody of Sir Hugh Waterton who was created Governor of them and the king’s children, John and Philippa, in July 1402.

On 1 February 1406 the boys were transferred to Pevensey Castle under the guardianship of Sir John who received an allowance of 500 marks a year from the March estate for their upkeep.

On 1 February 1409 they were transferred to the custody of the Prince of Wales, but their time in Sir John’s care created a lasting bond; March would later make Pelham a trustee of his estates and would accept a life annuity from him for his Sussex properties at Drayton and Chichester.

Edmund would find a more stable life under Henry V. Although he upset the king with his choice of bride, he remained one of his most trusted councillors, accompanying him to France and never making any assertion to the throne. He carried the sceptre at Queen Catherine’s coronation and became part of Henry VI’s regency council. He died aged 33 of the plague in Ireland.

The king: James I of Scotland (1415)

On 22 March 1406, the eleven-year-old James, heir apparant of Scotland, was taken prisoner by English pirates whilst trying to reach France. His elder brother David had been murdered and his uncle, the Duke of Albany, had his eyes on the throne, so the king had sent James away on the pretence of furthering his education, though Henry IV joked:

‘Of course, if the Scots had been our friends, they would have sent the young man to me for his education, as I know the French language.’

Within weeks of being in England, James’ father died and, now king, the boy was far too valuable to send back to his own kingdom. For the next 18 years, James remained a hostage in England although, after a period in the Tower of London, he retained his own household of Scottish nobles and continued to communicate with Scotland through ambassadors.

His uncle was in no rush to have him freed, refusing to pay the ransom the English king had set despite arranging for his own son’s ransom to be paid in 1415. His expenses were paid for by the English king and his education fostered a love of sports, music and poetry, inspiring him to write The King’s Quire. On reaching maturity he became part of Henry IV’s court, living between Windsor and London.

Henry IV’s death in 1413 changed James’ position at court. With a deep suspicion of his Scottish prisoners and a need to assert his authority in his new kingdom, Henry V moved the Scottish king to the Tower of London on the very first day of his reign.

By February 1415 he was at Pevensey Castle under Sir John’s custody, who received a grant of £700 on 22 February 1415 for the care of his royal prisoner. James remained in Sussex for just under a year and there is no reason to suggest that Sir John did not treat him as well as he had treated his other political prisoners.

James was moved on to other castles and in 1420, thanks to Henry’s interests in France, his importance grew. He crossed the Channel to France with Henry V, was a prominent guest at Catherine of France’s coronation as Queen of England on 23 February 1421 and escorted Henry’s body back from France in September 1422.

His ransom was finally paid in 1424 and after marrying the woman who had inspired his poetry, Joan Beaufort, he returned to Scotland. Unfortunately, life there would not end well. Having learnt his method of kingship in England, the Scottish nobles were resistant and he was assassinated in 1437, reportedly stabbed ‘to upwards of 30 wounds, some of which went through his heart’.

The witch: Joan of Navarre, Dowager Queen of England (1419-1420)

Pevensey Castle had formed part of the queen’s dowery for much of the 13th century, but when Joan of Navarre arrived there on 15 December 1419 she did so not as a guest but as a prisoner accused of ‘compassing the death and destruction of our lord the king [Henry V] in the most treasonable and horrible manner that could be devised’. She had been accused of being a witch.

It was not an accusation that was made lightly, nor one that was received without a great deal of concern. Even by the turbulent standards of the medieval period, her sudden arrest signified a remarkable fall from grace for a woman who was the daughter of the King of Navarre, mother of the Duke of Brittany, wife of one King of England and step-mother to another.

Joan came to England and married Henry IV on 7 February 1403. The union is generally accepted as a love match, with the two having become acquainted during Henry’s time in Brittany where Joan was the wife of the duke, John IV. On John’s death Joan served as regent for her ten-year-old son, but gave up the position to marry the King of England. The marriage was happy and although they did not have any children of their own, she had a good reputation with her stepchildren including the Prince of Wales, who often called her ‘his dearest mother’. In 1415, now as Henry V, he even trusted her to act as his regent in England whilst he was in France.

By 1419 their relationship had changed. It is possible that the imprisonment of her son, Arthur of Brittany, had soured their bond, but the accusation of sorcery by her personal confessor, Friar Randolph in August 1419 was still unexpected.

What really lay behind the accusation was that Joan was a woman of considerable wealth at a time when the king was a man in need of money. Henry IV had granted his queen a dowry of £6500 per year, a huge increase of £2000 to what was usual, including the wealthy manors of Leeds, Havering and Nottingham. The moment that the arrest was made on 29 September 1419 Joan’s lands were forfeited to the crown and a new stream of income became available to the king.

We know that throughout her imprisonment Joan was treated well and that she was allowed to bring her own servants and entertain guests, including her youngest stepson Humphrey, duke of Gloucester. She was moved from Pevensey on 8 March 1420 and taken on to Leeds Castle in Kent where she spent most of the rest of her imprisonment. She was never charged, a sure sign that no one ever really took the accusation seriously, and was finally released in July 1422, with the king, wishing to clear his conscious, ordering that ‘as ye will appear before God for us in this case to restore the queen wholly of her dower’. Henry died six weeks later and Joan returned to a quiet life, dying at Havering on 10 June 1437.

No longer at the forefront of England’s sea defences, Pevensey found a new purpose under the Lancastrian kings. With their loyal servant, Sir John Pelham, in charge they knew that the castle was a safe and impenetrable location for the state’s most valuable and politically sensitive prisoners.

Want to visit Pevensey Castle?

Pevensey Castle is run by English Heritage. Check out their website for details of when to visit.

Main photograph by By Prioryman (talk) CC BY-SA 3.0,