Today marks the 551st anniversary of the Battle of Tewkesbury, the final battle of the second phase of the Wars of the Roses. In terms of the number left dead it was not the bloodiest of the conflict, but it was one death in particular that made the difference – that of Edward of Lancaster. 1 Also known as Edward of Westminster and Edward, Prince of Wales

Edward of Lancaster and the politics of his birth

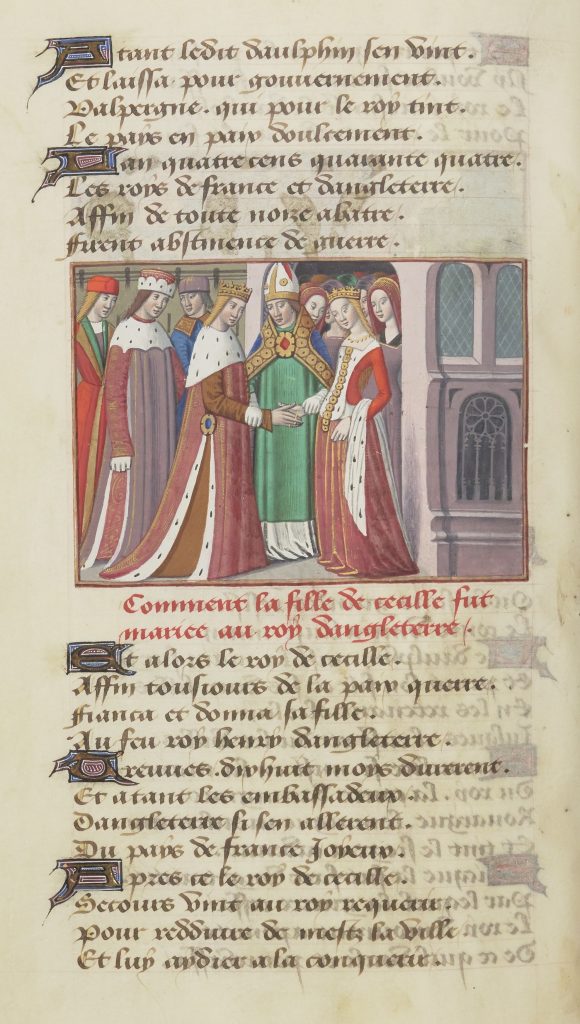

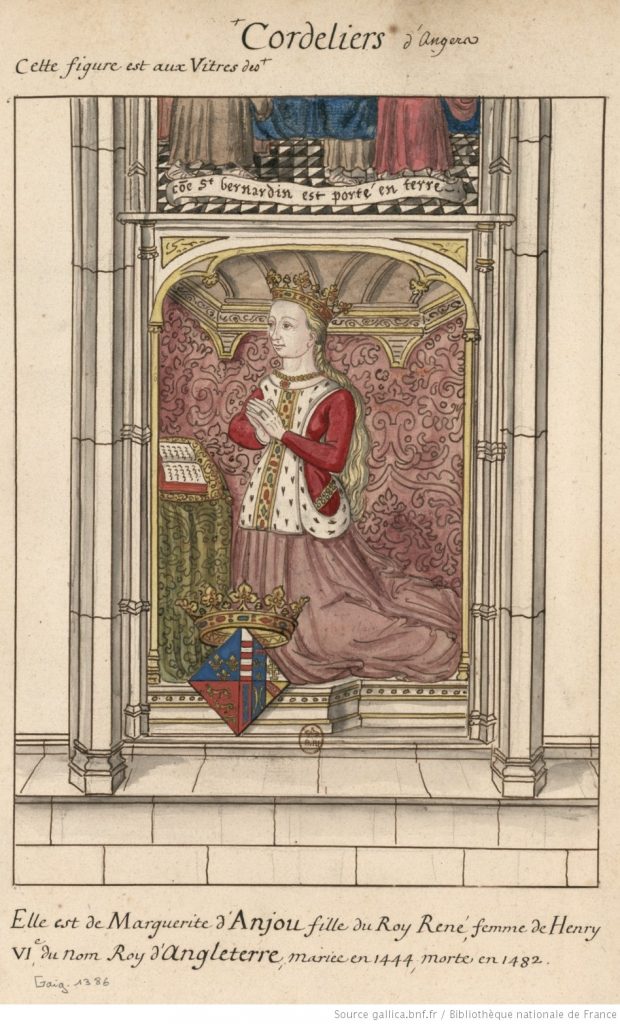

By the time of Edward’s birth at Westminster on 13 October 1453, Queen Margaret was already unpopular in her adopted land. She was born and raised in Anjou, and was only 15 when she married Henry VI of England in 1445. The union had been arranged by Charles VII of France as part of a peace treaty. It was an inauspicious start; the magnates relied on the conflict for their wealth plus it got worse when the King’s Council discovered that rather than receiving a dowry from the French, England had actually surrendered their claim to the lands of Maine and Anjou. Margaret has been identified as the instigator of this – Henry himself wrote that ‘our most dear and well-beloved companion the queen…[had] requested us to do this many times.’

There is little doubt that Margaret made some mistakes in those first few years of her marriage. She fulfilled her obligations of influencing Henry to the benefit of the French, plus she relied on a small group of advisors. But in truth, the scene had already been set before her arrival. Henry VI was already determined upon peace with France and the politics of the court had been founded long before she arrived. Her advisors were those that her husband had already shown favour to, resulting in the alienation of an important section of the court. Equally, there is no evidence that she ever intended to be anything more than a traditional queen consort and her first years in England were filled with the usual intercessory duties.

The problem was her husband. In moments of clarity, he was weak and ineffectual, but he was also the victim of bouts of insanity that left him catatonic and completely unable to rule. In the power vacuum that resulted, the rivalry that pre-dated Margaret’s arrival in England between the Dukes of Somerset and York strengthened, drawing in other members of the nobility and the queen, with deadly consequences.

Margaret came from a line of dominant and politically active women and in contrast to her feeble husband, she was described as ‘a grete and strong labourid woman, for she spareth noo peyne to sue hire thinges to an intent and conclusion to hir power.’2John Boking to Sir John Falstaff, 1456 Well educated and inspired by her mother and grandmother who had both acted as regent of Anjou, she expected the same for herself when Henry fell into a catatonic stupor in August 1453.

Edward’s birth two months later was a catalyst for the troubles that followed. While Henry had no heir, Richard, Duke of York was his closest relative and had an eye on his throne (Henry had half-brothers but they were by his mother and not from Henry V). Now, there was a barrier to his ambition.

York’s solution, if temporary, was to have himself established as Protector. For Margaret this was signalled a move to disinherit her son and she set herself firmly against the proposal.

Edward of Lancaster and the rumours over his paternity

The fact that Edward was born whilst his father was incapacitated has raised speculation for centuries, particularly as Margaret was now 23 and there had been no sign of a previous pregnancy. In the highly charged world of 15th century politics, Margaret’s enemies were quick to spread rumours that her child was either a bastard or changeling. The Duke of Somerset was the chief suspect of being the boy’s father, followed by the Earl of Wiltshire, but whichever, they chief message was that Margaret was a whore. The rumours spread fast, with one chronicle reporting that ‘The quene was defamed and desclaundered, that he that was called Prince, was nat hir sone, but a bastard goten in avoutry…’.

All this was not helped by the fact that when Henry woke up 17 months later his initial response to seeing his son was said to have exclaimed ‘he must be the son of the Holy Spirit’. In truth even the anti-Angevin Milanese Ambassador who reported this recognised that ‘these may only be the words of common fanatics, such as they have at present in that island.’3Prospero di Camulio (Milanese Ambassador to France) to Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan

There is a weight of evidence that suggests he was only ever Henry’s son. Presuming that Edward was a full term baby, she had fallen pregnant at the very beginning of January 1453 when Henry was still sane and able to father a child.

What’s more, during the next eight months he never questioned that the child was his, rewarding the messenger who brought him the news:

‘…grant made by us to Richard Tunstall, knight, …esquire for our body, of 50 marks a year for term of his life, part of an annuity of £40 a year, granted by us for term of his life, … because, among other things, the said Richard gave us the first comforting report and news that our most entirely beloved wife the queen was with child, to our most singular consolation, and a great joy and comfort to all our true liege people.’ 4Parliamentary Rolls, 1455

Henry was feeble and easily led, but he did not doubt his wife’s fidelity and gave gifts of jewellery worth £200 and land ‘unto ourre moost dere and moost entierly belovede wyf the quene, whils she was withe childe with oure first begotene son the prince.’

Of course, we can not say with one hundred percent certainty that Margaret never became so desperate that she did not turn to her most loyal servant for the ultimate service, but she would have been treading a very dangerous path. Coincidences do happen, and it is likely that Margaret falling pregnant a few months before her husband became ill was exactly that. The rumours of Edward’s paternity were a political tool, much in the same way Edward IV’s own paternity would be questioned some years later.

Edward of Lancaster, Prince of Wales

Edward was created Prince of Wales in 1454 and for the first seven years of his life he was Henry’s heir apparent, recognised as such by parliament. That was to change on 25 October 1460 when, with the passing of the Act of Accord, he was disinherited.

Open warfare broke out between the Duke of York and the King’s men in 1455 and Henry VI’s capture in July 1460 gave the duke his chance to finally be rid of the barriers that stood between him and the throne. In a flamboyant and misjudged display of power, he made a claim to the throne through his decent from Edward III’s second son (although through the female line) as opposed to Henry’s decent from the third son. It seriously backfired. The nobles were not prepared to remove an anointed king, but it was agreed that they would discuss it, but only with the permission of the king. A strong king would have resisted, but Henry, now obedient to whoever had control of him, allowed the discussion to take place. Within eight days, the decision was made that whilst Henry would be allowed to remain king for the rest of his life, his son was to be replaced in the line of succession by the duke and his decedents. 5 Payling, Simon, The Brief Triumph of Richard, duke of York: the Parliamentary Accord of 31 October 1460 retrieved 3 May 2022

If Margaret was familiar with the phrase, ‘I told you so’ this was her moment to say it. All of her fears had been realised – the duke was the threat she had always known him to be.

Margaret’s defence of her son now came to the fore and would dominate the rest of her life while he lived. With the help of Scotland’s queen regent (at the cost of the town of Berwick), Margaret made a counter attack which initially proved successful, and in December 1459 York was killed in a skirmish near Wakefield in Yorkshire. But the victory was short lived and three months later at the Battle of Towton on 29 March 1460, the Lancastrian army was smashed by York’s son, the earl of March. He seized the throne to become Edward IV.

Edward of Lancaster in exile

For the next ten years, Edward of Lancaster would live in exile, moving from place to place and court to court. He is known to have lived in Northumberland, Edinburgh, Bruges, Lorraine, Flanders and St Mihiel-en-Bar, but none were able or willing to provide him with the army he needed to launch an invasion of England to reclaim his inheritance. Henry VI, meanwhile, languished in the Tower of London.

Little is known of Edward during these years as he grew into maturity. The most commonly quoted opinion of him is by the Milanese ambassador to France who, in 1467, said that he ‘already talks of nothing but cutting off heads or making war, as if he had everything in his hands or was the god of battle or the peaceful occupant of that [English] throne.’ 6Prospero di Camulio, Milanese Ambassador to France Historians have used it to show him as a bloodthirsty tyrant in the making, but this is somewhat unfair. For one the Ambassador was anti-Angevin which makes his opinion somewhat suspicious, but equally, it is incredibly judgemental of a 14-year-old’s behaviour. Anyone with children today knows that many of them enjoy the glamour and thrill of watching Luke Skywalker and Darth Vadar go toe-to-toe, or the Hulk smash Loki into the floor. Childhood for a medieval prince was even more absorbed by warfare. From a baby he would have been immersed in the world of chivalry and knighthood, from the books he read to the toys he played with. He would have begun training when still a young child, and we know that Margaret took him to the battlefield at St Albans in February 1461 where he was knighted. He then knighted others before his mother gave him the task of announcing the fate of the Yorkist rebels, Sir Thomas Kyriell and Lord Bonville, who were summarily executed.7Griffiths, R A. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Edward of Westminster retrieved 3 May 2022 He was not quite eight. Small wonder if he talked about war and his hatred of the men who had stolen his crown.

Physically, not much is known about the prince. No portrait of him exists – all we have is one pencil drawing from the Rous Roll and a depiction of the Battle of Tewkesbury which may or may not feature him. We know that he needed to see a doctor when staying with his grandfather, Rene of Anjou8Griffiths, R A. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Edward of Westminster retrieved 3 May 2022 but, from his love of outside pursuits, we can ascertain that otherwise he was strong and active. In another quote often used to show his bloodthirsty nature, Sir John Fortescue, recalled that ‘as soon as he became grown up, [he] gave himself over entirely to martial exercises; and, seated on fierce and half-tamed steeds urged on by his spurs, he often delighted in attacking and assaulting the young companions attending him, sometimes with a lance, sometimes with a sword, sometimes with other weapons, in a warlike manner and in accordance with the rules of military discipline.’

Both of his parents were well educated, promoted literary projects and founded King’s College and Queen’s College, Cambridge. We can therefore surmise that Edward would have been raised in an atmosphere of academic thinking, reading and debate which may have influenced his own court had he ever become king.

Marriage to his mother's enemy

Whether they accepted it or not, the Lancastrian cause was dead. What would have happened to them is open to conjecture; perhaps, like James II and his decedents two centuries later they would have lived out their lives on the Continent as regal vagrants. However, in 1470 everything changed again when Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick fell out with Edward IV, led a failed attempt to constrain the king, and fled to France with his family in April 1470.

Edward would have understood that his bride would be chosen for him, but what he thought of Anne Neville, daughter of one of his mother’s most prominent enemies, is not recorded. Two years earlier, in January 1468, his mother had been in talks about a marriage with Marguerite, daughter of Louis XI of France, but now, with the same king’s encouragement, Margaret was eventually persuaded to join the heir to the English throne to the daughter of not just an earl, but the sworn enemy of the Lancastrian nobility.

Edward and Anne were married on 13 December 1470 when he was 17 and she 14. Doubt is often cast on whether the marriage was consummated, although ultimately it became irrelevant. It is possible, as some have surmised, that Margaret prevented it in order to have the marriage annulled once they were back on the throne; Edward was far too valuable a commodity to waste on an earl’s daughter. But it seems unlikely that Warwick would have committed to the invasion without the guarantee that his daughter would be queen.

Edward of Lancaster's death at Tewkesbury

Margaret and Edward returned to England on 14 April 1471 to news that Warwick was dead, killed at the Battle of Barnet that same day. It was a calamity, and for a moment they considered retreating back to France, but the Prince is said to have encouraged his mother on. For Anne Neville, her future was now bleak; without her father there was nothing to keep the queen from denying any consummation and annulling the marriage. Her only hope was that she was pregnant. She wasn’t.

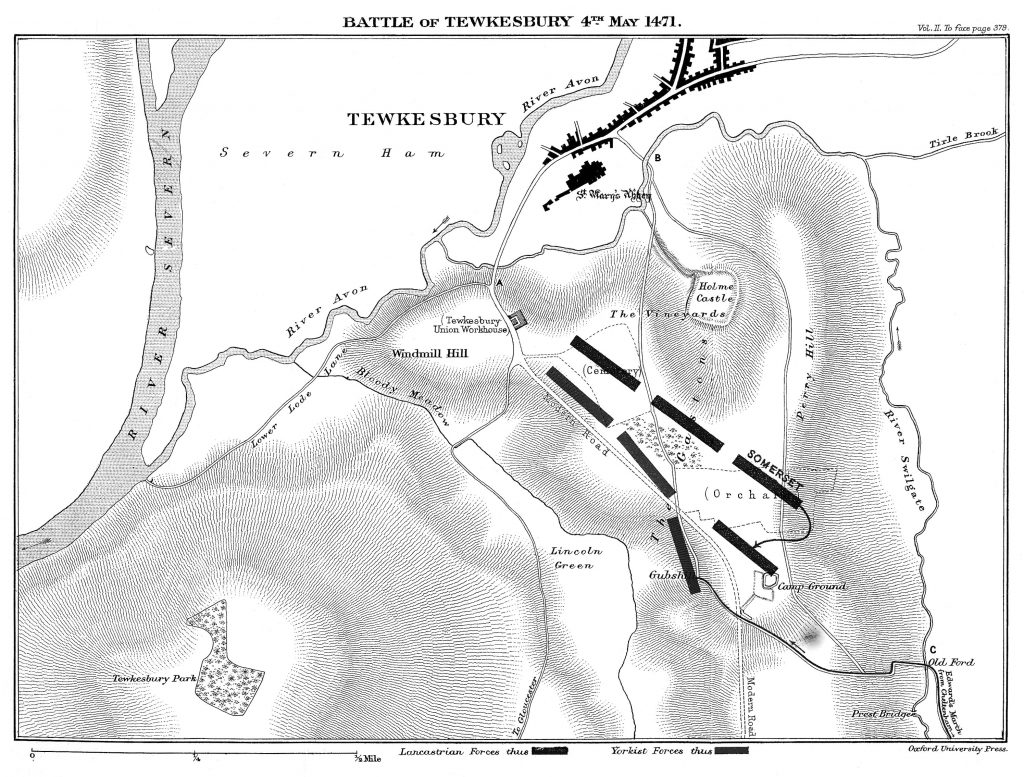

The Lancastrian forces of around 5000 men headed towards Wales to meet up with Jasper Tudor, the Earl of Pembroke, who was waiting on the other side of the River Severn. When they were refused entry to Gloucester, they headed for the crossing at Lower Lode, marching 24 miles in 16 hours9UK Battlefield’s Resource Centre: the Battle of Tewkesbury. Assessing their chances of crossing the ford before the York army arrived, the Duke of Somerset concluded that they would not make it without being trapped. He decided to stand and fight and ‘drew his men foorth into battaile aray, muche against thadvise of thother captaines, who thought best to tarry til therle of Pembrowghe showld coome.’10Polydore Vergil p151

The battle proved a disaster. Whilst Margaret watched from the Abbey tower, Edward led the centre section of the army into battle, but when the Yorkist foiled a surprise attack with huge loss of life, the Lancastrian army began to crumble:

‘…but whan the queue had not freshe soldiers to supply the places of wearyd and woundyd, she was overmatchyd of the multitude, and in thend vanquisshed ; hir company being killyd and taken almost every one.’11Polydore Vergil p152

Chroniclers record several stories of exactly how Edward died. William Shakespeare used the accounts of Polydore Vergil and Raphael Holinshed as his sources for Henry VI. Vergil writing in 1534, claimed that Edward was brought before Edward IV and struck down by the Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III), Lord Hastings and the Duke of Clarence:

‘Edward the prince and excellent yowth, being browght a lyttle after to the speache of king Edward, and demaundyd how he durst be so bowld as to enter and make warre in his realme, made awnswer, with bold mynde, that he came to recover his awncyent inherytance; here unto king Edward gave no awnswer, onely thrusting the young man from him with his hand, whom furthwith, those that wer present wer George duke of Clarence, Richerd duke of Glocester, and William lord Hastinges, crewelly murderyd; his corse, with the resydew of them that wer slane, was interryd in the next abbay of monkes of thorder of St. Benedict.’12Polydore Vergil p152

Holinshed, writing in 1577, said it was just Gloucester.

A second long-lived theory is that Edward was caught whilst trying to escape the battlefield and taken before his brother-in-law, George, Duke of Clarence who ordered his execution despite the young boy’s pleas:

‘…and the moste parte of the peple fledde awaye from the Prynce, by the whiche the feld was loste in hire party. And ther was slayne in the felde, Prynce Edward, whiche cryede for socoure to his brother-in-lawe the Duke of Clarence.’13 Warkworth’s Chronicle p18

More likely, however, is that Edward died ‘on the field’ abandoned by his soldiers, either fleeing or fighting for his life.

Margaret must have suspected the worst long before it was confirmed to her at Payne’s Place in nearby Bushley hours later. She was later captured and paraded through the streets of London. Henry VI was quietly put to death in the Tower but had he lived it wouldn’t have made any difference. Her fight was gone – it died on the battlefield of Tewkesbury with her son.

Further Reading

Day, Nora. A Fresh Look at the Battle of Tewkesbury, The Tewkesbury Historical Society. Retrieved 3 May 2022

The ‘Crimes’ of Richard III – Myth vs Fact, Richard III Society of Canada, retrieved 3 May 2022

Griffiths, R A. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Edward of Westminster, retrieved 3 May 2022

Lee, Patricia-Ann. Reflections of power: the dark side of queenship. Renaissance Quarterly Vol. 39, No. 2 (Summer, 1986), pp. 183-217

Payling, Simon. The Brief Triumph of Richard, duke of York: the Parliamentary Accord of 31 October 1460, retrieved 3 May 2022

Quinn, Nicole. The parentage of Edward Lancaster, 2013, retrieved 3 May 2022

Quinn, Nicole. The personality of Edward of Lancaster, 2013, retrieved 3 May 2022

Ross, Charles. The Wars of the Roses: a concise history. Thames and Hudson, London, 1994

UK Battlefield’s Resource Centre: the Battle of Tewkesbury, retrieved 3 May 2022

Virgil, Polydore. Three Books Polydore Vergil’s English History, Comprising The Reigns Of Henry VI., Edward IV., And Richard III. Edited by Sir Henry Ellis, The Camden Society, London, 1844

Warkworth, John. Chronicle of the First Thirteen Years of the Reign of King Edward the Fourth, Edited by James Orchard Halliwell, The Camden Society, London, 1839