The Georgians (1714-1837)

Monarchs of the Georgian Period

The Georgian era was a period of immense change, with the coming of a new royal house, political upheaval, industrial developments and literary creations.

The arrival of the Hanovarians

The 1701 Act of Settlement has to be one of the most important (and probably discriminatory) pieces of legislation passed in Britain. Its primary aim was to prevent a Catholic from inheriting the throne and its immediate impact was to wipe out the eligibility of over 50 claimants.

The last of the Stuart monarchs, Queen Anne, died on 1 August 1714, two months after the death of Electress Sophia of Hanover, her heir. The two had been on bad terms and it was rumoured that the Electress died after receiving a particularly angry letter from the queen which brought on a stroke.

George was never a popular monarch. He was often portrayed as unintelligent and was disliked for his treatment of his wife. However, whatever his faults, he continued to be seen as a better choice than the Catholic Stuart heir, James Stuart (the Old Pretender), and the throne passed peacefully to his son, George II, on his death in 1727.

Despite attempts by the Jacobite rebels to reinstate the Stuarts, the Hanoverians would remain the monarchs of Great Britain and Ireland until Queen Victoria’s death in 1901.

The rise of the Prime Minister

The monarch’s chief advisor was a long established role at court, appointed and dismissed (sometimes even executed) at the whim of the king. However, after 1689 the position became tied to the growing power of parliament and the role of first minister became, in all but name, the head of government.

One consequence of George I’s lack of English, frequent visits to his homeland of Hanover and disinterest in British politics, was that this role became even more significant, and in turn, more powerful.

From 1721, this role was occupied by Sir Robert Walpole, who obtained such a grip on power that he was able to appoint all other ministers, dispense royal patronage, guide policy and control the Treasury. He is now regarded as Britain’s first Prime Minister, although his official title was First Lord of the Treasury and the term was not officially used until 1885. Walpole, himself declared:

‘I unequivocally deny that I am sole and prime minister.’

Although subsequent monarchs attempted to regain the power they had once had over the chief minister, the post was solidified by George III’s mental illness when the current Prime Minister, Lord North, declared:

‘In critical times, it is necessary that there should be one directing Minister.’

The Battle of Culloden (1746)

The Stuart claim to the throne had seemed all but over by 1745. James Stuart’s three attempts at invasion had all ended in failure and he was not content to live out his days in Rome.

But his son, Charles Stuart (the Young Pretender), was not yet done and in September 1745 he won a decisive battle at Prestonpans against the king’s forces. Realising the seriousness of the invasion, the king’s cruel and spoilt son, the duke of Cumberland, was dispatched to Scotland where the Jacobites had unexpectedly returned to, and met them on 16 April 1746 at Culloden Field.

What resulted was a messy, uncoordinated and badly planned attack on the Government forces. The Highlanders lost over 1000 men compared to Cumberland’s 50 and Charles, misunderstanding his commander’s tactics and believing himself betrayed, fled back to France.

The Industrial Revolution

For centuries Britain’s industry had revolved around textiles based in homes and small workshops, powered by people and animals. By the 1770s this had changed.

First invented in 1712, James Watt’s remodelled steam engine would revolutionise British industry, allowing for bigger machines, deeper coal mines, large mills and faster methods of transport.

With that, however, came social changes. Although it is important not to romanticise cottage industries, the new factories meant a drive down in wages and an increase in dangerous working conditions. Migration into the larger cities rapidly increased and living conditions became increasingly worse.

The Romantic poets and the birth of the English novel

The Georgian era saw the rise of the Romantics, a movement that celebrated emotional responses to art, literature, architecture, music and reasoning. Its members included William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron and Percy and Mary Shelley.

The first novel, Robinson Crusoe, was published in 1719, giving birth to a new and popular medium. The era sees some of the most famous novels in English: Gulliver’s Travels (1726), The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), Pride and Prejudice (1813) and Frankenstein (1818).

The period also saw one of the greatest philosophers on female rights, Mary Wollstonecraft, the mother of Mary Shelley.

Key people

- Jane Austen

- Robert Burns

- Olaudah Equiano

- Anne Lister

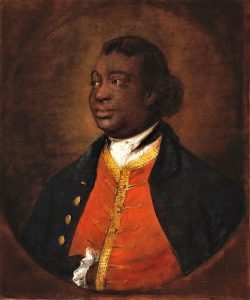

- Ignatius Sancho

- Adam Smith

- Charles Edward Stuart (the Young Pretender)

- James Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender)

- James Watt

- Sir Robert Walpole

- The Duke of Wellington

- Mary Wollstonecraft

Key events

- 1714 Electress Sophia of Hanover dies 2 months before Queen Anne

- 1715 Jacobite rising attempts to make James Edward Stuart king

- 1718 The pirate Blackbeard is killed

- 1719 First novel is published Robinson Crusoe

- 1721 Robert Walpole becomes the first Prime Minister

- 1733 Downing Street becomes the home of the Prime Minister

- 1746 The Battle of Culloden

- 1751 Britain changes its time

- 1788 The Times is published for the first time

- 1796 A cure for smallpox is discovered

- 1785 Power loom invented

- 1815 Battle of Waterloo

Read more from our magazine

Ignatius Sancho (c1729-1780): composer, writer, mentor and friend

When a two year old boy named Ignatius Sancho arrived in England in 1731, an orphan and a slave, it would have been hard for