Monarchs of the Stuart period

The Stuart period is best remembered for the turbulent years of the English Civil War and the execution of King Charles I. But it was also a great age for science, saw England and Scotland united under one monarch and witnessed the birth of Great Britain.

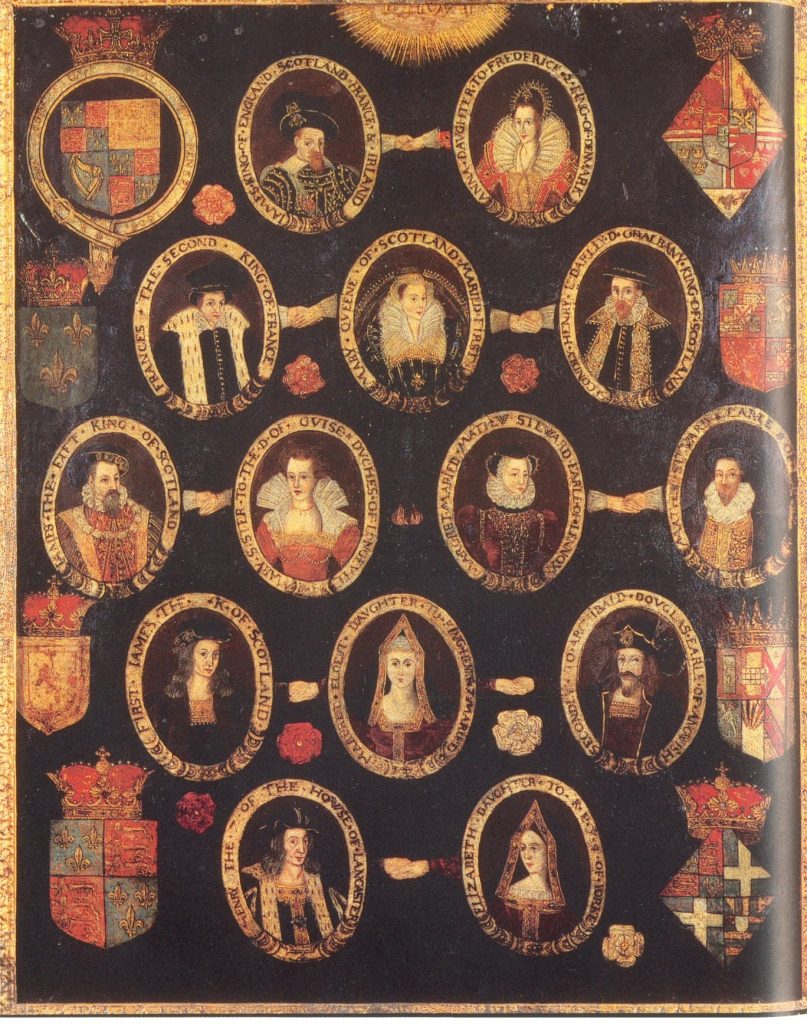

The Union of the Crowns

James VI of Scotland traced his lineage back to Henry VII through his daughter Margaret, and on the death of the childless Elizabeth I, James inherited the throne of England.

James had ascended to the Scottish throne at the age of one when his mother Mary was overthrown by her Protestant nobility. For his safety, he was raised at Stirling Castle by the earl of Mar, and was given a Protestant education at which he excelled. When he was 12 he finally came to Edinburgh as king, but four years later in 1582 he was abducted and held captive for a year in what became known as the Raid of Ruthven. However, by 1584 he was able to assert himself and his rule was both effective and relatively peaceful.

His accession to the English throne was surprisingly peaceful thanks to the work of Sir Robert Cecil who had spent the last two years planning for the eventuality. James entered London on 7 May 1603 to a rapturous welcome and was crowned on 25 July, uniting the two nations under one king.

However, James’ attempts to fully unite this two kingdoms did not succeed. From 1604 he styled himself as the King of Great Britain, but England’s parliament refused to recognise the term in law and there was also opposition in Scotland. It was not until 1707 that Great Britain was born.

In November 1605 James narrowly escaped assassination when a group of Catholic conspirators were discovered attempting to blow up Parliament. Now known as the Gunpowder Plot, James declared that it intended the destruction of ‘not only… of my person, nor of my wife and posterity also, but of the whole body of the State in general.’ His survival was greeted with great relief and is still celebrated in Britain as Bonfire Night.

The wars of the three kingdoms (1639-1653)

When Charles I dissolved parliament in March 1629 it would not meet again for another 11 years. Known as the personal rule, it marked a schism in the relationship between king and people that descended into the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

The opening conflict was the Scottish Bishops War of 1639 and 1640 which erupted when Charles I tried to impose a version of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. The following year, Ireland erupted into rebellion in support of Charles against his Protestant opponents. Hundreds of Protestants were mascaraed, leading to rumours in England and Scotland that the same fate awaited them if the king was allowed to have control of an army.

After the 11 year hiatus, the parliament that Charles called to pay for his Scottish campaign lasted only 3 weeks and became known as the Short Parliament. However, by November 1640 he was forced to summon parliament again who quickly passed an Act to prevent the king from being able to dissolve it again. Trouble immediately flared between the two parties: Charles was a fervent believer in the divine right of kings plus a stricter sect of Protestants (known as Puritans) began to take power in Parliament.

Armed conflict finally broke out in England in 1642 and over the next four years the king’s forces (the Cavaliers) were gradually defeated. Charles surrendered to the Scottish army in 1646 but spent the next two years trying to make a pact with the Presbyterians in the English Parliament and the Scots to save himself and the institution of the crown. Known as the Second English Civil War, it ended in Charles’ execution for treason against the people on 30 January 1649.

The Interregnum and Restoration

Charles II was declared King of Scotland on 5 February 1649, although he was still barred from entering the country and military defeats over the next three years left him a king without a country.

What Britain got instead of a king was a military dictatorship. The New Model Army purged parliament of any royal sympathisers, creating what was known as the Rump Parliament which, in turn, declared Britain to be a Commonwealth and Free State. This remained in power until 1653 when Oliver Cromwell used the army to take power. He was deeply religious and felt it was his duty to purge daily life of excess and immorality. For the next 8 months he governed via an assembly supported by the army, but it was bedevilled by infighting and Cromwell was forced to dissolve it. Instead, the Instrument of Government was drawn up, appointing a Lord Protector as the head of government. Although elected, the position would be held for life, and Oliver Cromwell was duly appointed on 15 December 1653. After a short attempt at governing through parliament, Cromwell divided England into 11 districts each of which were governed by a Major-General who were only accountable to Cromwell.

Meanwhile, Charles II had fled to the Continent where he found refuge in the Hauge with his sister, the Princess of Orange and in Paris. When both forged alliances with England, he was forced to move to Spain and seemed destined to lead a leisurely life in exile.

Cromwell’s death in 1658 marked the end of the Commonwealth. His son’s tenure as Lord Protector was a disaster and in 1660 parliament issued an invitation to Charles to return as king. All traces of the Interregnum were erased and Cromwell was exhumed and his head stuck on a spike as a traitor.

The Glorious Revolution

When James II succeeded his brother Charles II he had already converted to Catholicism. At first he was accepted, but when he began to install policies that favoured Catholics and built alliances with France, the Protestant ruling classes became concerned. This was further emphasised in 1688 when James’ second wife, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a son, who, it was announced, would be raised a Catholic. When James’ prosecution of seven Church of England Bishops failed at the end of June 1688 and riots broke out in England and Scotland, it was decided that James would have to go.

This time Parliament did not seek to remove the king completely. Instead they wrote to James’ son-in-law (and nephew) inviting him and his wife, Mary, to take the throne. William arrived in November 1688 and gathered support as quickly as James lost it. Two days before Christmas, James fled to France.

As part of their accession, William and Mary were required to concede power. The Declaration of Rights required the monarch to acknowledge the sovereignty of parliament and to govern according to ‘the statutes in Parliament agreed on.’

The scientific revolution

Scientific thinking underwent a radical change during the 17th century as the discipline became distinct from philosophy, astrology and alchemy.

Many scientists were interested in several different areas, none more so than Sir Christopher Wren who was not only an architect, but also a mathematician, astronomer and anatomist. After the destruction of much of London during the Great Fire of 1666, Wren was commissioned to rebuild 51 churches and St Paul’s Cathedral.

Chemistry became recognised as a science in its own right, with Robert Boyle now considered as its father. The relationship between pressure and volume was discovered by Richard Towneley and Henry Power, but it the law is still remembered by Boyle’s name.

Until the 17th century astrology was the dominant discipline in studying the stars. However, astronomy now made an appearance with men such as Edmond Halley who catalogued the celestial southern hemisphere, analysed the distances between Earth, Venus, and the Sun and calculated the orbit of comets with such precision that one was named after him.

Key people

- Mary Beale

- Robert Boyle

- Margaret Lucas Cavendish

- Sir Robert Cecil

- Oliver Cromwell

- Guy Fawkes

- Edmond Halley

- John Milton

- General Monck

- Sir Isaac Newton

- Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales

- Sir Christopher Wren

Key events

- 1611 Publication of the King James Bible

- 1620 The Pilgrim Fathers set sail for America

- 1649 The execution of Charles I

- 1653 England gains its first written constitution

- 1662 The Royal Society is founded

- 1666 The Great Fire of London

- 1667 Paradise Lost by John Milton is published

- 1687 Principia Mathematica by Sir Isaac Newton is published

- 1694 The Bank of England is founded

- 1701 The Act of Settlement is passed

- 1707 Scotland and England are united as Great Britain

- 1712 Thomas Newcome invents the steam engine

Read more from our magazine

Queen Anne and her son, William Duke of Gloucester

Princess Anne and her son, William duke of Gloucester Sir Godfrey Kneller c1694 I’ve always found this painting particularly poignant. It depicts Princess Anne (later

How Anne Hyde changed the course of history

Had Anne Hyde lived beyond 13 March 1671 she would have been Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland, and yet she remains relatively forgotten, lost