Had Anne Hyde lived beyond 13 March 1671 she would have been Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland, and yet she remains relatively forgotten, lost amongst the more famous Stuart consorts. Married to James, duke of York, the younger brother of Charles II, she did not live to see him become king, but her influence had already set him on a path to disaster.

Anne Hyde, the gentleman's daughter

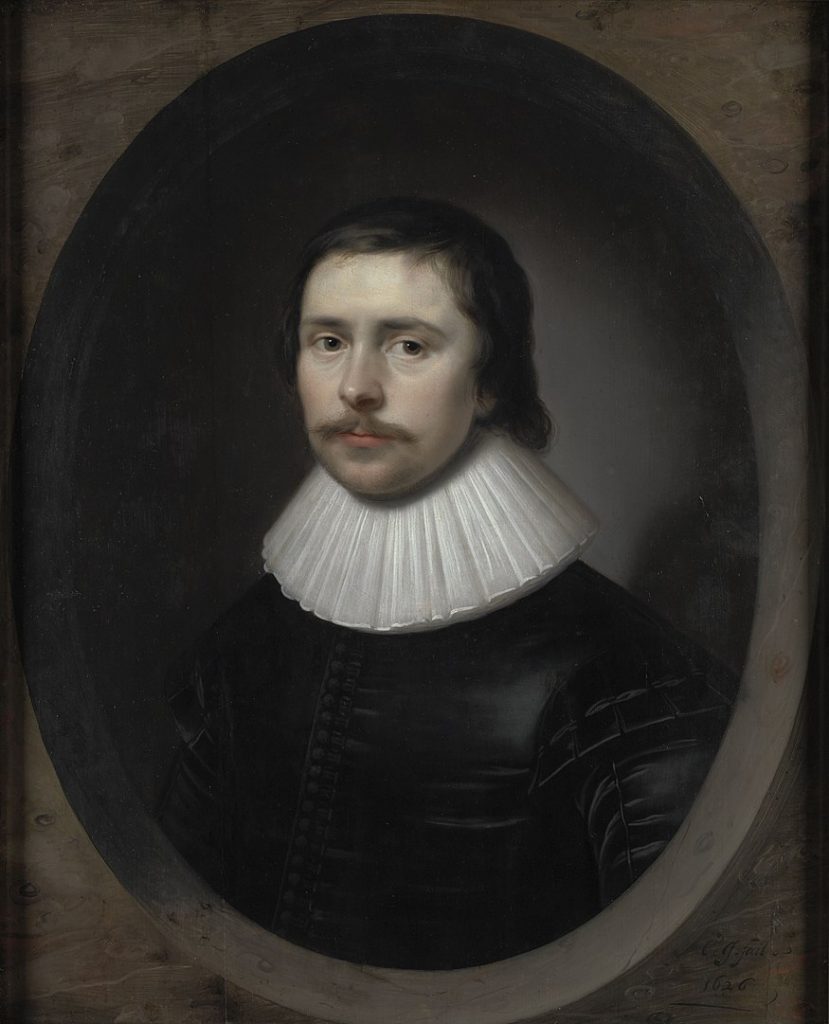

Anne was born on 12 March 1637 near Windsor, the eldest daughter of a country lawyer, Sir Edward Hyde. In the turbulent politics of the War of the Three Kingdoms that saw king pitted against Parliament, the family’s fortunes shifted with that of the royal family.

Although Anne’s father had initially begun his parliamentary life as a critic of the king, he gradually changed his stance and his elevation to Chancellor of the Exchequer and member of Charles I’s Privy Council in 1643 aligned the family with the king for better or worse.

By 1645 it was worse and when Hyde left Oxford in March it would be another three years before Anne would see him again. First he fled to Jersey with the Prince of Wales, where he stayed for two years despite the prince moving on to Paris after two months. In September 1648, he re-joined the prince, now King Charles II, in The Hague but it was June 1649 before Anne and her family joined him, meeting him at Antwerp as he was on his way back to Paris.

Anne lived in Antwerp until the end of 1651 at which point she moved to Breda, and by 1655 she had been appointed as a maid of honour to Mary, the Princess of Orange and Charles II’s younger sister. Despite the honour, Anne’s father opposed the move: he was fully aware of the licentious nature of the court and how vulnerable his seventeen-year-old daughter would be to the temptations she now faced on a daily basis.

Anne was popular at the court. Although not considered a great beauty, numerous contemporaries describe her as having ‘a great deal of wit’ and she was well liked by Mary. Exiles from England filled the Dutch court and contemporary letters, including one by the king himself, named several contenders for Anne’s affections, including Sir Spencer Compton, the son of the Earl of Northampton. Her own aunt, Barbara Ailesbury, joked that the ‘unkind gerle hath robed me of all my Gallants’ and the Memoirs of the Count of Grammont (written by the Count’s brother-in-law, Anthony Hamilton) recalled that ‘there were none at the court of Holland who eclipsed her…’

It would not be long, it seemed, before Anne would catch herself a husband far above the aspirations of a gentleman’s daughter.

Anne Hyde and the duke of York

That husband would be James, duke of York, who, as Charles’ heir, held a special place at court, even if that court was in exile. Although he was a notorious womanizer like his brother, it was expected that his marriage, when it happened, would be to the benefit on England.

Anne first met James in 1656 when she accompanied the Princess of Orange to Paris to visit the Dowager Queen Henrietta Maria. The queen’s dislike of the Hyde family was so fervent that not only had she opposed Anne’s appointment as a maid of honour, but Anne’s father informed Lady Stanhope on 16 July 1659 that he had tried to persuade Anne not to go to Paris because of it. James was entranced by her luscious chestnut hair, voluptuous figure, wit and intellect and there is little doubt that he attempted to seduce her, but opinion is divided as to whether Anne submitted. It is possible that they became lovers as early as 1656 with their relationship continuing in secret for the next three years via his occasional visits to his sister’s court in The Hague, but it is more likely that it wasn’t until 1659 that their affair began.

Anne Hyde and the King

Charles had already had an illegitimate son in 1649 with his mistress Lucy Walter, and then a daughter in 1651 with Elizabeth Boyle, but both had known their place and although Charles acknowledged the children, there was never any thought of marriage. James, however, decided to do things differently, perhaps due to the influence Anne had over him. Sometime in November 1659 the duke entered into an agreement to marry Anne, which, being consensual on both sides and witnessed, was legally binding.

When the Restoration returned Charles to the throne six months later in May 1660 it was already too late for James to go back. Anne had become pregnant sometime in January 1660 and she was beginning to show. There is doubt around when James told his brother what he had done, but it was not received well. Initially, Charles refused to give his consent, her father (now the Earl of Clarendon and thinking of the damage it would do to his reputation) urged the king to imprison her, and James waivered. However, when it became clear that the duke was trapped, Charles tried to find the positives of the situation, telling Clarendon that she was:

‘a Woman of a great Wit and excellent parts, and would have a great power with his brother, and that he knew she had an entire obedience for him her Father, who he knew would always give her good counsel by which he was confident that naughty people which had too much credit with his brother and which had so often misled him, would be no more able to corrupt him, but that she would prevent all ill and unreasonable attempts, and therefore he again confessed that he was glad of it.’

As a result, Anne and James were married on 3 September 1660 at her father’s house in the Strand with only the chaplain and two witnesses present. But that was not the end of it.

The wrath of the Stuart dynasty

Anne gave birth on 22 October, being forced to defend that the child was James’. In November the Queen Mother made a dash from France to try and persuade her son to renounce the marriage, questioning Anne’s honour in a letter to her sister, the Duchess of Savoy:

‘To crown my misfortunes, the Duke of York has married without my knowledge, or that of the king, his brother, an English miss who was with child before her marriage. God grant that it may be by him. A girl who will abandon herself to a prince will abandon herself to another. I leave for England to-morrow to try and marry my son the king and unmarry the other.’

The Princess of Orange continued her opposition until her sudden death from smallpox on 24 December 1660 and, to aid his escape, several friends embarked on painting Anne as a whore who they had all slept with. According to the memoirs of Anne’s father, one of them, Sir Charles Berkeley, claimed ‘that he was bound in conscience to preserve him from taking to wife a woman so wholly unworthy of him; that he himself had lain with her; and that for his sake he would be content to marry her, though he knew well the familiarity the Duke had with her.’ James waivered again, but by December the marriage was public and there was no going back.

Anne Hyde and the loss of a foreign alliance

James’ rashness was to have enormous consequences. Charles’ foreign policy revolved around appeasing the French and even his own marriage to the Catholic Portuguese princess, Catherine of Braganza, was at the behest of the French king. Cash-strapped, envious of Louis XIV’s autonomy and beholden to his generosity, Charles had expected that James’ position on the marriage market would help him secure financial independence from parliament and grow England and Scotland’s place on a global stage. Charles may have used James to forge a stronger alliance with France, or, in order to appease Parliament after the disappointment of his own Catholic marriage, to a Protestant princess.

Instead, James had tied himself to an unnoteworthy English nobody who offered nothing to Charles or his security.

Anne Hyde, the duchess of York

Anne’s marriage began with tragedy when the child she had been carrying at her wedding died of smallpox in May 1661 aged 7 months old. She was also finding it difficult to gain respect at court with Samuel Pepys recording that same year that ‘The Duke of Yorke lately matched to my Lord Chancellor’s daughter, which doth not please many.’

Anne was, however, resilient. She was noted for her intelligence and astuteness, and the wit that had made her popular in The Hague did not desert her, winning her the friendship of the king. The historian Sandra Sullivan has shown how Anne used her portraits to emphasis ‘her beautiful hair, the power of her hands and … the power of her intellect, since in holding a book in a society where literacy was restricted to an elite, books were not only symbols of the contemplative life, but symbols of power.’

Like it or not, Anne was the duchess of York and she made sure that she took her place. James said of her that ‘her want of birth was made up by endowments, and her carriage afterwards became her acquired dignity’, but the French Ambassador, Le Comte de Cominges, agreed, reporting on 7 August 1664 that Anne:

‘…is as worthy a woman…as I have met in my life, and she upholds with as much courage, cleverness and energy the dignity to which she has been called, as if she were of the blood of the kings…’.

Pepys took a different view although his reliability is debatable. He never seems to mention her without some cutting remark and on 24 June 1667 he reported that:

‘…besides the death of the two Princes lately, the family is in horrible disorder by being in debt by spending above 60,000l. per. annum, when he hath not 40,000l.: that the Duchesse is not only the proudest woman in the world, but the most expensefull; and that the Duke of York’s marriage with her hath undone the kingdom, by making the Chancellor [Anne’s father] so great above reach, who otherwise would have been but an ordinary man, to have been dealt with by other people; and he would have been careful of managing things well, for fear of being called to account; whereas, now he is secure, and hath let things run to rack, as they now appear.’

Tragedy and betrayal

What she expected of her marriage remains a mystery. They still seemed to be affectionate in 1663 when Pepys witnessed them at the theatre on 5 January 1663 showing ‘…some impertinent and, methought, unnatural dalliances there, before the world, such as kissing, and leaning upon one another.’ However, the historian Allan Fea believed that this was a case of over-acting by the pair to try and fool the court into believing that they were still in love.

If she had also expected fidelity then she was quickly disappointed. Almost as soon as they were married James began a year-long affair with one of her maids of honour, Goditha Price, as well as with Anne Carnegie, countess of Southesk. More would follow and in 1665 he began a 13-year-long relationship with Arabella Churchill which would produce four children, including two sons, all of whom lived to adulthood.

This must have been particularly painful for Anne. Of the eight pregnancies she had over the 11 years of her marriage, only two children survived to adulthood, both girls. In 1667 she witnessed the death of her two sons, James duke of Cambridge and Charles duke of Kendal, within a month of each other.

Despite their lack of children, James did not seek to divorce her. Perhaps this was more to do with his transition to the Catholic faith than because of a sense of loyalty to his wife, but whatever the reason, the lack of a Protestant male heir would change the course of history.

Her daughters were both raised as Protestants on order of the king and it is logical that the same policy would also have applied to a boy. A Protestant son would have eased the need for James’ deposition but even if he had been removed, the Glorious Revolution under the leadership of William of Orange would not have occurred. No William and Mary; no Queen Anne; no Hanoverian dynasty; no Queen Victoria.

Ill-health and decline

1668 saw a rapid decline in Anne’s health which coincided with the birth of Arabella Churchill’s first child. Lady Chaworth informed Lord Roos on 5 May 1668 that Anne ‘breaks out so ill of her face visibly and of her leg again as people talke – that she was yesterday blooded and kept her bed’. Most damagingly, Anne began to over-eat, causing her to put on a huge amount of weight. In his poem Last Instructions to a Painter Andrew Marvell cruelly wrote of her:

Paint her with oyster lip and breath of fame

Wide mouth that ‘sparagus may well proclaim

With Chanc’llors belly and so large a rump,

There (not behind the coach) her pages jump.

Lady Chaworth wrote again in March 1669 that rumours were circulating that the duchess had been behind a break-in of the duke’s closet in order to find love letters, but she declared that the idea was foolish as ‘alas she is both to [sic] wise, and to [sic] much indisposed to be so curious, being all this time broken out in several places of her face and body, and now in phisick that she is not seene.’

It seems probable that Anne was suffering from depression brought on by her husband’s infidelities, the death of her children, her inability to bear an heir and her wrestling with her conscience over her faith. Life at court was taking its toll on her mentally and the constant pregnancies on her physically.

Anne's conversion to the Catholic faith

Anne’s most serious effect on James, and the one she had the most control over was in religion

She had been raised a staunch Protestant, described by her tutor, Dean Morley, as ‘devout and charitable as ever I knew any of her age and sex’, but by the age of twelve she was already beginning to question her faith. Various reasons for her conversion have been offered, from the need to regain her husband’s affection to the influence of Queen Catherine, but ultimately, the decision seems to have been a personal choice and one that coincided with the decline in her health. By 1669 she had converted and in August 1670 she was formally received into the Catholic church although it was kept secret on order of the king.

The consequences of this action were considerable. Anne was known to be strong willed and determined and long before 1669 James had developed a reputation for being influenced by her. Samuel Pepys wrote on 30 October 1668 that he and Thomas Povey had agreed ‘that the Duke of York, in all things but in his cod-piece, is led by the nose by his wife’ and even the king was said to have joked that James was a hen-pecked husband. She was far more intelligent than James and she had read, questioned and reasoned her way to her conversion, writing in August 1670 that:

‘I only in short say this for the changing of my Religion, which I take God to Witness I would never have done if I had thought it possible to save my Soul otherwise.’

It seems only logical that she would then use those same arguments to convert her husband to save his soul, which he finally did sometime in 1669, although he did not reveal the fact until forced to by the 1673 Test Act.

Several historians have also taken this view. Murice Ashley believed she was responsible as did John Miller and John Callow. It is impossible to say that James would not have converted without Anne’s influence as he had shown interest in Catholicism when in exile, but he had resisted his mother’s earlier attempts to convert him and he had angrily protected his brother Henry from her when she had tried to convert him too. But if Anne’s influence was as strong as rumour said, despite his infidelity, it is likely that she had a large part to play in his final decision.

It would be a catastrophic one. James’ conversion would have huge implications on both his own future and that of the three kingdoms. Although his succession as king on Charles’ death was peaceful, it did not last, and James’ attempts to move both court and parliament towards Catholicism led to the Glorious Revolution, his deposition and, ultimately, the end of the Stuart dynasty (when his daughter Anne finally died childless in 1714). Anne Hyde had again changed history. Had James never married her, had she not converted, had she not influenced him, then his own conversion was not guaranteed. A James II who had retained his Anglican faith would have changed the course of not only his own reign, but would have pathed the way to his son with his second wife becoming James III.

Died little beloved

Anne was never well again after 1668. She continued to get pregnant and watch her children die and she continued to eat. She was pregnant for the last time in late 1670, from which she herself admitted that she never fully recovered.

Her cause of death on 31 March 1671 aged only 34 is debated. The idea that she was suffering from breast cancer is widely quoted although there does not seem to be any contemporary evidence of it. She had dined the night before with her brother-in-law but then collapsed leading to a diagnosis of appendicitis by some historians. Lastly, there is the ongoing illness that had affected her face and legs and may have led to her ultimate demise.

Whatever the cause, Anne’s body doesn’t seem to have been treated well, being ‘tost and flung about and every one did what they would with that stately carcase.’

Gilbert Burnet, the biased Anglican Bishop of Salisbury, claimed that she ‘died little beloved. Haughtiness gained many enemies…[her] change of religion made her friends think her death a blessing at that time.’

Although her friend and nurse, Margaret Blagge, recorded that ‘none remembered her after one weeke [sic], none sorry for her…’, Anne’s influence on history is significant. How James’ life would have turned out without her is another ‘what-if’ of history, but she had such a huge impact on his availability to make alliances, his inability to have a living Protestant male heir and his change in faith, that history would certainly not have been the same without her.

Further reading

Abernathy, Susan. Anne Hyde, Duchess of York. 11 January 2019.

Earle, Peter. The Life and Times of James II. Book Club Associates, London, 1984.

Fea, Allan. James II and his wives. Methuen and Co, London, 1908.

Hamilton, Anthony. Memoirs of the Count of Grammont.

Henslowe, JR. Anne Hyde Duchess of York. T W Laurie, London, 1915.

Melville, Lewis. The Windsor Beauties: ladies of the court of Charles II (revised edition). Victorian Heritage Press, USA, 2005.

Miller, John. Anne (née Anne Hyde), Duchess of York. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys. 1893 edition.

Speck, WA. James II and VII. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

Sullivan, Sandra Jean. ‘Representations of Mary of Modena, Duchess, Queen Consort and Exile: Images and Texts’. Unpublished PhD thesis, University College London, 2008.

Zuvich, Andrea. Anne Hyde – the commoner that became a duchess. 12 March 2013.